Gedoemd tot kwetsbaarheid (Doomed to Vulnerability)

First published in 2005 - How can we ever tell this to our great-grandchildren, the story of those final months of 2004? What will we remember about it? The knifed body lying on Linnaeusstraat? The skeletons that came out of the closet afterwards? The perpetually moving lips of politicians and intellectuals? The silence in the city? The tone, the new tone that was suddenly in vogue? How can one begin to tell?

First published in 2005 - How can we ever tell this to our great-grandchildren, the story of those final months of 2004? What will we remember about it? The knifed body lying on Linnaeusstraat? The skeletons that came out of the closet afterwards? The perpetually moving lips of politicians and intellectuals? The silence in the city? The tone, the new tone that was suddenly in vogue? How can one begin to tell?

Theo van Gogh was murdered by Mohammed B. in Amsterdam on the morning of November 2, 2004. The gruesome act shook the country to the core; no matter how politicians and journalists tried, however, no civil war broke out along the North Sea. Ethnic relations were polarized to be sure, but the country did not descend into tribal warfare between natives and immigrants. Yet during the weeks after Van Gogh’s murder, the peace was a hard thing to keep.

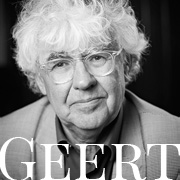

In reaction to the oversimplified commentary and opportunistic bunkum spouted by politicians and journalists, Geert Mak wrote Gedoemd tot Kwetsbaarheid, in which – only a few months after 2/11 – he tried to pour oil on the troubled waters.

From the very first sentence, the author assumes a tone that allows for perspective: “How can we ever tell this to our grandchildren, the story of those final months of 2004?” Then Mak begins chopping away at the standpoint that the Netherlands is “at war”, a statement attributed by one journalist to the vice-premier at the time. No, Mak says, the murder of Van Gogh was the work of one religious fanatic, a disturbed individual; it did not constitute the implosion of our multi-ethnic society. Mak counters the excitable tone of many politicians and journalists with calm statistics and a lesson in Dutch history. In late 2004, he states, there were some 900,000 Muslims living in the Netherlands, most of them Turkish and Moroccan. “Of all these Dutch ‘Muslims’”, Mak writes, no more than twenty percent ever visited a mosque on a regular basis. Most of them were familiar with Islam only from a distance.” Mass radicalization, a specter evoked by many at the time, was a complete myth.

While many in the Netherlands fear that the large-scale influx of foreigners poses a risk for our celebrated “secular humanism”, Mak denies that the solution lies in transforming the country into a “cultural fortress”; all that would accomplish would be to reduce the complex problems of our day to “one huge, domestic paranoid fantasy”.

Gedoemd tot kwetsbaarheid is an impassioned plea for levelheadedness. In it, Mak does his best to stem the tide of inflammatory rhetoric, the fear-mongering and the half-truths which spread like a virus through the public debate in the aftermath of 2/11.

Not surprisingly, Gedoemd tot kwetsbaarheid prompted a deluge of reactions. In a second pamphlet, Nagekomen flessenpost (Belated Messages in a Bottle), Mak not only replies to the criticasters, but also rebuts many of the commentators who had so readily misconstrued his words. The Netherlands, he notes, is in mourning, “and all of us must live with that. The grisly murder of Theo van Gogh localized the pain more clearly: the safe and secure Netherlands of twenty-five years ago has in many places become a thing of the past, the familiar feeling is gone, the predictability vanished.” Upon which Mak closes with this summons: “There is only one possibility: the dynamism of hope. We have no alternative.”

In the daily newspaper Trouw, columnist Sylvain Ephimenco referred to him as a “prattling populist”. In De Volkskrant earlier this year, Dutch Liberal Party advisers Luuk van Middelaar and Kees Berghuis spoke of “foul insinuations”.

Geert Mak shrugs it off. “Mudslingers always need a target, and I’m it, I suppose. But the rise of the extreme right-wing is a problem for both Holland and Europe as a whole. I wanted to issue a warning: be careful, this can lead to nasty situations.”

His role as pamphleteer added a new dimension to the image of the refined “nostalgist” attributed to the author of bestsellers such as Hoe God verdween uit Jorwerd and De eeuw van mijn vader. “I was livid. Someone had to speak out. It’s my job to write books and to help sort out ideas. I wouldn’t be worth my salt if I didn’t do that, would I?!” – Geert Mak in an interview with Niek Pas in NRC Handelsblad.

First published in 2005

First published in 2005

Paperback, 94 pages

Uitgeverij Atlas

ISBN: 9789045013824

Out of print

Foreign translations:

German: Der Mord an Theo van Gogh

Original title: Gedoemd tot kwetsbaarheid

Translated from Dutch by Marlene Müller-Haas.

Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2005.

First published in 2005 - How can we ever tell this to our great-grandchildren, the story of those final months of 2004? What will we remember about it? The knifed body lying on Linnaeusstraat? The skeletons that came out of the closet afterwards? The perpetually moving lips of politicians and intellectuals? The silence in the city? The tone, the new tone that was suddenly in vogue? How can one begin to tell?

First published in 2005 - How can we ever tell this to our great-grandchildren, the story of those final months of 2004? What will we remember about it? The knifed body lying on Linnaeusstraat? The skeletons that came out of the closet afterwards? The perpetually moving lips of politicians and intellectuals? The silence in the city? The tone, the new tone that was suddenly in vogue? How can one begin to tell?  First published in 2005

First published in 2005